What Ann Patchett Taught Me About Sharing Like-Grief

You are a stranger to my life, but a soulmate to my pain.

The Ann Patchett Instagram post came to me via email, from a friend and former colleague.

Ann, author extraordinaire, is bouncing her dog Sparky in her arms. She is telling her followers that Sparky has an enlarged heart. Her dog of 12 years, who has also been a part of her famous Nashville bookstore, Parnassus, is going to die. She pauses, her eyes cut to the right. She musters a mighty load of gumption before she continues, “When that happens, I am not going to be able to tell you, so I am telling you now. I will release this video when that occurs because I am not going to be able to talk about it then.”

“This is my present self, protecting my future self,” she concludes.

While my husband and I cry rivers, Ann Patchett, bestselling author of Tom Lake, Bel Canto and numerous other well-known books, delivers her calm message, only once needing to pause to compose herself.

“Been there, Ann, done that,” I say over and over to myself as I watch the video several more times.

Only pet owners can truly understand the depth of the pain that she masks as she speaks.

I have had people, who remain a little dumbfounded, say to me that the passing of their dog was as difficult—or even more difficult—a passage than the death of some of their loved ones. Mothers, fathers and husbands are among the losses of which they speak.

Because of my long trail of losses—mother, father, husband, sister, brother, nephew, niece and best friend—I can speak with authority and tell them I understand. I don’t understand why it is true, but I do know it can be true.

I lost my Cockapoo, Charley, to the same enlarged heart as Sparky.

“Charley deserves someone he knows, in his own home. It is my gift to him,” my vet said on the day we determined he would come to my apartment to facilitate Charley’s passing. I vividly remember the bellow I let loose when the vet lifted my little dog’s lifeless body, rolled him into a towel and headed to the elevator of my apartment building. Eight years later I still query the gloom that hangs around on the balcony, where Charley used to sit.

People talk too much about unconditional love and not enough about why it is profound. Love given, no strings attached, is like walking by a mirror and always seeing pretty. Charley took me uncut and raw. I was never critiqued by him. If I came home late, grew distracted, and failed to say a proper hello, he’d crawl up in a corner and sleep till I remembered. And when I remembered, he’d wag his tail and roll over to have his belly rubbed.

But maybe even bigger than Charley’s capacity to give love was his capacity to receive it. When he needed to ride in his eventual stroller instead of walk, he would stop, turn his face to the stroller and wait to be air-lifted up. Upon his return, he’d sit atop his perch and woo to the doormen. It was his call for them to come outside their cubby and give him a pat on the head. They always did. Charley stalked love like prey. Just one pat and then he would cruise the landscape for another tap from someone else.

Charley slept hard in his spot on the sofa on his last day. He seemed to know his fate and like all days of his living, he accepted it as his biography already written. He entrusted to me, with no questions asked, his pathway to dying. I sat and watched him sleep, until the vet arrived and subsequently took him away.

In the days after, a lonely hole went everywhere with me; it was the space where he had been. I went from room to room more aware of his absence than maybe I had ever been of his presence. That may be why the loss feels so unique. No one else centers themself on the axis of your life’s minute hand and shadows every move.

Losing Charley spawned a grief that resembled none of my other deaths. There are a fair number of people who can’t possibly understand.

“Get another one,” some well-meaning folks encourage as though the kitchen mixing bowl got broken.

Other friends shuffle and stutter, anxious to change the subject because they are smart or polite enough to not express what they may think.

“It’s a dog,” I imagine passes through their mind.

Years ago I read a book or an article about grief. It changed me.

Contrary to the soothing remarks that frequently come our way, such as “give it time,” or “time heals all,” there was a contrarian view expressed.

Grief hangs around forever. Even if it grows less painful, even if the look of it changes, it’s still there.

In the beginning, it finds a soft spot and cuts right through the flesh. While the gash comes back together and eventually heals, there’s a new kind of skin that holds it together. Mighty tender in the beginning, but as time goes by the off-white sheath of scar tissue bonds the split parts together. When I touch an age-old scar, it feels different. There may be little to no sensation, or the pain may shoot up again. But while scar tissue gussies up the wound and dresses me up to go out, it never changes what happened below the surface.

When I was five years old, I fell. Some bully boys were going to use a kitten as a softball. I ran to retrieve the kitten and fell on all fours. I screamed both in pain and awfulness. They brought me the kitten, retreating like cowards when they saw my mother running out of the house.

I probably needed stitches, but my rural Missouri mother taped on a new bandage every day until the wound closed. Some 65 years later my right knee still carries those marks.

A long time passed, maybe the rest of my life, before I could tell the story. Time did not heal all, but like a salve, time did eventually provide an anesthetized bridge, that allowed me to recall, touch and tell.

When my sister lost her oldest son, she was torn apart because no one close to her could share the exact same pain. Her only solace was the eventual therapy circle where all the other members had also lost a child.

However, it did give her comfort to tell me word-for-word everything that occurred in each of the sessions.

The mornings after those meetings were the only times I ever heard her breathe in a regular cadence again.

Sharing like-grief exposes the freshly healed or years-old scars of the survivors. The more jagged the healed edges, the more hope of normalcy the scars offer to the newly-wounded.

While sympathy and love can flow abundantly from the kind human beings who reside in our lives, it is the purity of exactitude that engenders empathy, and thus comfort. You are a stranger to my life, but you are a soulmate to my pain. There are times when suffering my same hurt is more important than loving me forever.

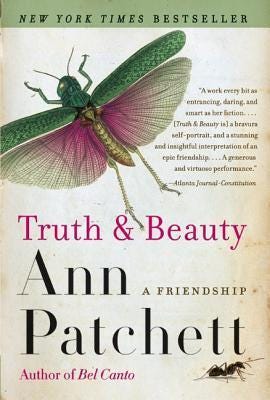

When I read Ann Patchett’s memoir Truth & Beauty, about her friendship with the Irish American writer Lucy Grealy, who died at the age of 39, I sighed with gratitude.

An author, known by me only through her writing, had felt the same pain I felt when I lost my best friend and sister.

When I flipped the last page over, I was sorrier than usual to be finished with a great book. I flipped the book over and ran my hand over the front cover, something I had not done in a very long while.

“I love Ann Patchett. I love Ann Patchett. I love Ann Patchett because Ann Patchett loved Lucy Grealy so deeply and so well and so unconditionally.”

That’s the letter I wanted to write to Ann Patchett, but I didn’t write that letter to Ann Patchett. I let time dilute the passionate notion down to dormancy.

But I spoke again and again about the book and author to my friend, Carol, who had gifted me the book and who had also forwarded Ann’s Instagram post to me.

Two losses of two strangers cross in cyberspace and the pages of a book.

When Ann Patchett lost Sparky, we all lost him with her.

Thank you, Tara.

So glad you enjoyed it!

Thank you for being my supportive friend.

I did not know someone could read so promptly!