Little Boy Bleu, my designer-poodle mix, ran toward the heap of bedclothes bunched on the top of the hill. When he got about three feet away from the mound, he started barking like a lunatic. While maintaining his distance, he stretched his head and neck as far forward as possible to get a better whiff. His legs extended behind him in a straight plane. He appeared to be flying. There was not one muscle in that little cockapoo body that was not tense. With a pair of goggles, he could have been Snoopy commanding the doghouse airplane.

“Bleu! Come!” I screamed though gritted teeth, trying to be calm. Other concerned strangers crooned and called as well.

“Come, Bleu, come baby,” I quickly remembered to call in a sweet melodic tone.

I was relieved to see him running toward me. I decided to attach his leash until we got to our destination. I watched carefully to see if the bundle started to move. It didn’t.

I noticed the makeshift pile of linens on most morning walks, but Bleu, normally on a leash, could never wander close enough to investigate. The human under the heap was a regular resident of that grassy patch, but I had never actually seen him. Frequent Central Park visitors knew that he (we do presume he) was a late sleeper and woke sometime after we had left the park and moved on with our day. As early morning passers-by, we never violated the space. The unwritten rule became a practice for many reasons, but primarily because no one knew the temperament or demeanor of the person underneath the quilts and blankets and things.

The unanswered questions made the lines around him as clear as a white picket fence.

The unwritten code of restraint accommodates the broad spectrum of human circumstance that exists in Central Park. For an instant, I imagined how a name-dropper downtown would handle the same situation on their elite street. Something raw inside me wiggled, and I was reminded that I liked to live in a world that did not filter for sameness.

I heard the voice of the dog trainer coming up behind me. He was bellowing a hollow “hello” to anyone holding a leash. The park was his target range for new clients. I noticed that he always paid special attention and softened his voice for new puppy owners. I watched Bleu from the side as he moved closer to me and tried to eye the man’s cane, as it tapped the pavement with an irregular rhythm.

The story of the old-grouch coach got re-told quickly to eager new dog owners, as every regular had already heard the history. Apparently, he was on the Mike Douglas show in the ’60s and wrote a book on dog training. They say it’s still available on Amazon, but I never actually checked to see if that was true.

“Who wants the book?” asked the woman who first told the story to all of us morning dog people. “Rumor has it, he tells you to hit the dog with the leash if he doesn’t heel on command.”

The harsh suggestion had elicited an involuntary jolt of disgust from the sleepy crowd, and it had never failed to produce the same effect with each new recital.

I passed Marianna on the way to the puppy play area. She always carried her monstrous bag of recycled bottles and wheeled her cart of essentials in front of her. She had just freshly groomed herself in the park bathroom. Her hair was tied in a topknot, and someone had given her some new socks. They were grey and dusty pink. After telling her I liked them, she cased my face for a split-second scan. As soon as she realized I was not giving cash she moved on.

In the improvised puppy park, we met up with the regulars. There are no official dog runs in Central Park; dogs can be off-leash from 9:00 PM to 9:00 AM, but made up cordoned-off areas are created when low fences are found, so that little puppies can be lifted over to play in groups. While they learn basic commands, they are safe in the enclosure. The Brazilian mother, whose small music prodigy children play regularly at Lincoln Center, brings her Havipoo. Her children sometimes show up in their pajama bottoms and snow boots if they aren’t due for an early morning rehearsal. Susan and her wife Kathleen, an Episcopal priest, alternate their visits with Max, the chunky puppy, who is well on his way to 35 pounds. And Ingrid, the engineer, jumps over the fence with her labradoodle that is also growing bigger than expected. It’s a coffee klatsch of dog owners who resemble young mothers chatting away about crate training, treats and chew toys.

Finished with puppy play, I decided to let Bleu run off-leash again as we we made our way to Poet’s Walk. I threw the ball, he ran for it, brought it back, dropped it, lost it, and finally got it stolen by another dog.

I am always gob smacked with amazement and awe when I reach the entrance to Poet’s Walk. The towering elms stretch out their branches and wave me in. Their leaves stir through the sunlight to create a ground show of shadows worthy of entry fees. I presume the dance is designed exclusively for me, as no one else has watched from my angle at exactly the same second. That little thrill has always put an extra buzz into my morning prayers.

Lives are stacked neatly just a little over a half mile in three directions. Some of the most densely populated land in the world borders this haven, and yet I can tilt my head and clearly hear the cicadas chirping from the trees. A man wandered by with his camera and commented to me and to no one, “I just saw a red-breasted.” A red-breasted what I wondered for half a second and then moved on.

I saw the sun swinging high its beams above Central Park South. One day I’d noticed that one of the billionaire buildings was ripped in half with a bolt of light and a swab of shadow. Those buildings, built during De Blasio’s tenure, block some light that historically fell on the park, so I was not sorry to see the illusion of breakage. One determined citizen, by the river, on the West side, literally stopped the construction of a very high skyscraper for a while. I can only paraphrase her famous quote, but she indicated that the light should belong to everyone, and not just to the rich people who can buy multi-million-dollar apartments in very high buildings.

Moving through those grounds as a regular is like walking down the main street of a small town. I nod once, then smile at the familiar faces. Sometimes I know the name, sometimes I don’t. If they have a dog, I usually know their dog’s name even if I have not registered or forgotten theirs.

I was always a bit embarrassed by that lapse until the morning I was able to put sense to the phenomenon. Standing on the edge of one of the haphazard spaces where some of the older dogs gather, I noticed that the volume of the voices went above the murmur only when asking Fido or Noodle or Einstein to fetch, to come or to stay. Noodle fetched, but then mischievously ran wild with the ball. Fido never came so I heard his name 100 times a morning, and Einstein, the massive Newfoundland, ONLY stayed. I sometimes wondered why he was continually told to stay in the same place where he had first plopped upon arrival.

The dogs leash up at 9:00 AM, their restrictions making room for the horses, carriages, and pedicabs that provide accommodations for those who choose to wheel through the park. Sometimes I can hear sweet French being spoken in the distance. Tourists? Native New Yorkers who are practicing for a later European trip? Maybe they will picnic later in the day on the grass lawns that have been watered and safeguarded during the 12-hour doggie romp time. No dogs allowed, EVER, on those green carpets.

Bleu and I headed home.

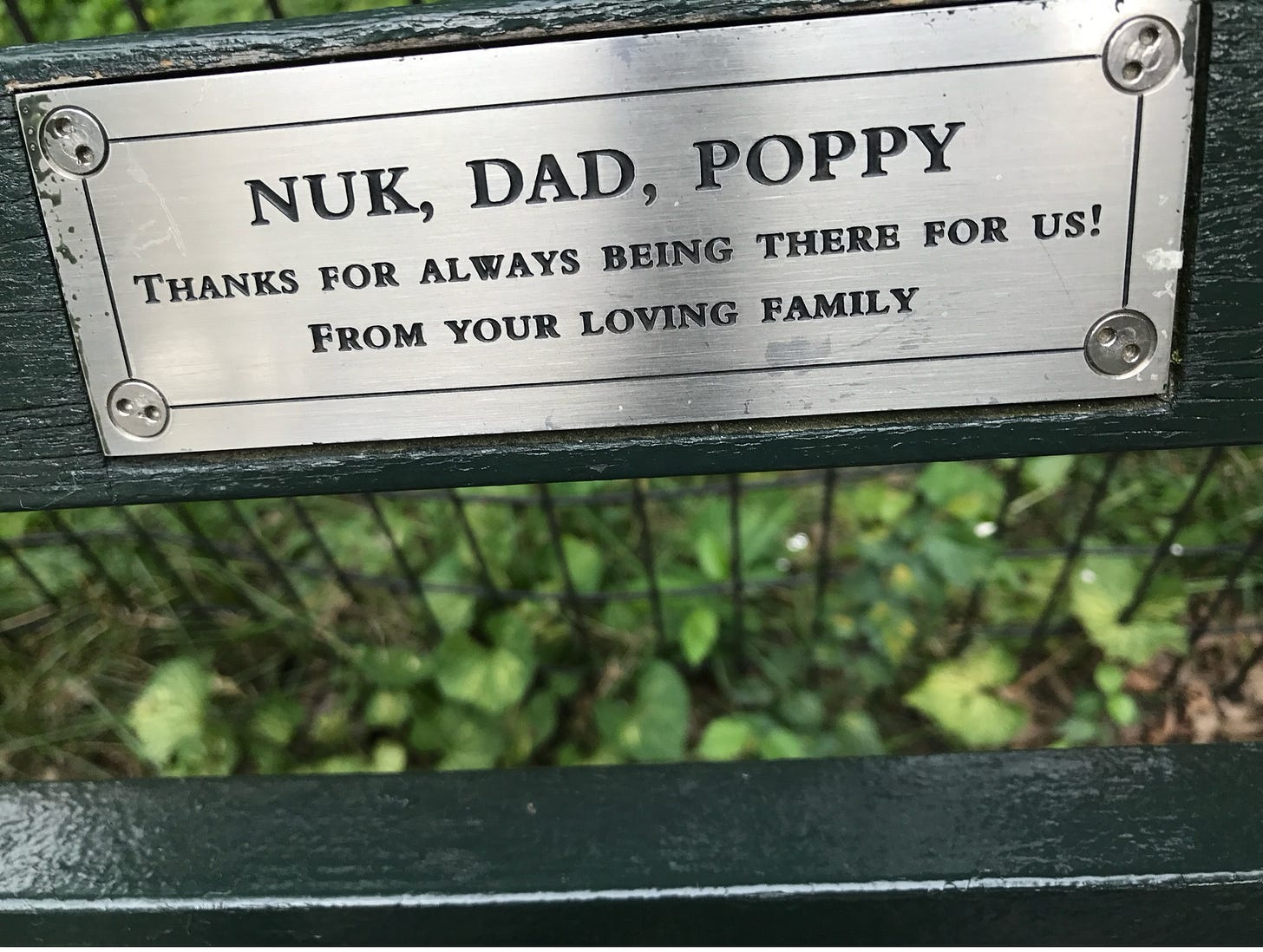

The little plaques on the park benches commemorate birth and death and animals and seasons. They line up along most paths and offer sneak peeks into strangers’ lives. To walk along and read them slows down the day and brings important life events into everyday routine. I have made up my own stories for some of the little phrases.

Can’t you just picture that family? Is it the WASPy nickname “Nuk” that puts you on a sailboat off Nantucket? Is it the phrase “Thanks for always being there for us” that sets just the right tone of restraint? I think it was blue blood and money that etched the words on the plaque. Of course I don’t know, but I like to imagine.

That’s all. The secret of that summer is not for the public, but the pewter-colored fixture teases us with intrigue, makes our minds wander. What was it? Did two people fall in love? Was it the summer of their first child? Or was it simply a fling that ended and all that is left is this little reminder?

And 2014 for me? I shutterbug through photos on the iPhone. I stop on May. Not quite the summer, but the month of beginnings.

There is a photo of me with two of my great nieces. In the photo I stare into the camera, chic sunglasses and all, leaning against one of two country club columns, my elbow perched out, hand on waist, head tilted to one side. My great nieces stand on either side, smiling broadly, also leaning against the columns. One facing in, kicking her leg backwards like a showgirl, the other, facing the camera, arm swung behind her back. I’d flown to Missouri to give a party for my great niece, who was graduating from high school. The party was a series of many, since her mother’s diagnosis of stage four breast cancer, just four years earlier. That summer, along with all the others since 2010, had been an extended family scramble, grabbing at moments and making them festivities. We touched each little passage and passed it around like a pure gram of gold, aware more than ever, of the weight of its scarcity.

You look back at pictures and figure the time. My niece would live two years more after that photo, dying at Christmas.

What would we all do if we knew the time of our dying? Would the days be different? Where would we go? Who would we see?

That last day of living, what would it be?

That last day of living, what would it be?

I would start in this park with my husband and dogs. I have traveled the world and nothing and nowhere brings me home like this place. Home is where the inside of me relaxes and longs for not one more thing. It is where I am satiated, actually filled to the brim with ease and restfulness. Yet life, human, canine, and otherwise, darts to and fro, telling me animated stories, with their activity and dress and stride.

Executives fast-pace toward their 10,000 daily steps while placing buy and sell orders based on Hong Kong’s morning. New mothers run by with newborns in jogging strollers; musicians play and the lonely folks find company at the dilapidated tables outside Quotidian Café.

I have shared the reservoir run with Jackie O, unsuccessfully trying to peek through those big dark glasses. I have scared myself silly getting lost in The Ramble, and I have arrived too early in the morning at Strawberry Fields and feared I was seeing too much behind certain trees.

Later in the morning, Bleu and I arrived in Strawberry Fields, and stopped for a moment at the John Lennon memorial. I read that Yoko, from the Dakota apartment they shared, can see the commemorative mosaic. I always look toward their building and wonder if she might be standing at the window. I hope she can clearly see IMAGINE, the word she had sculpted in the circular pathway dedicated to the approximate spot where they scattered John’s ashes.

“Imagine,” I whispered to Bleu, who settled down for a minute, but cared not a bit for my moment of reflection.

Hard to imagine, but, for the most part, we all get along in this space. Imagine that 42 million people a year step on the earth of these 843 acres. I think it is the grand lady, Central Park herself, who imposes the moral code that generally makes us all behave.

They say there are thin spaces on earth, places on earth where God feels nearer and clearer to us. They are generally considered to be spiritual retreats that drench us in nature with the organic benefits of solitude and quiet.

Ah, but the miracle of Central Park is that she buffers out the sound of the sirens, plays the song of the red-breasted for the interested birders, and provides a somewhat harmonious space that is otherwise primed for human collisions.

Ah, but the miracle of Central Park is that she buffers out the sound of the sirens, plays the song of the red-breasted for the interested birders, and provides a somewhat harmonious space that is otherwise primed for human collisions.

While we do not know the individual under the blankets, we do know he is a regular and we know if we respect his white picket fence and sleep times, we should be safe. The old dog trainer’s story provides a legacy that adds a pinch of permanence. And knowing names, be they human or canine, Marianna or Fido, makes the passerby my neighbor.

Uniformity is not required to be included in Central Park’s boundaries.

Central Park is my thin place, right next to God and all the chaos.

When I would be planning to come home from college, my mother would always say,

Come as you are, stay for as long as you need or as long as you can.

thank you for reading and staying in touch.

Oh my Goodness! What. POWERFUL piece ! So many truths whether you are walking your beloved dog in Central Park , or that your niece died . Very powerful, and the way you wrote it simply captivated so many emotions and thoughts . Thank you , Lynne . Love , Elaine